Peering across Georgia’s expansive Alazani Valley, grasping the rail and shuffling carefully across an icy wall, I look up to the snow-packed peaks of the Caucasus Mountains. The mountains across the valley are enormous and so is the valley. The vast nation of Russia rolls away on the other side.

I’m standing atop part of a fortress erected in 1762 by King Heraclius II, designed to keep out the marauding Dagastani tribesmen. Georgians have been repelling invaders for nearly their entire history, and the spirit of resilience continues to define the national character today.

My careful maneuvering along the frozen wall during a February visit is my unexpected introduction to Sighnaghi, Georgia’s “City of Love.” The city sits on the western edge of Georgia’s largest wine producing area, and it’s our second stop on our EatThis!Tours’ day trip from the capital city of Tbilisi.

A Nation Fighting for Its Identity

Located south of Russia, east of the Black Sea, and northeast of Turkey, the tiny country of Georgia over the centuries has had to defend its sovereignty and identity from invaders from all sides. Today it remains formally independent and carries on a lot of trade and cultural exchange with Europe and the West (though its government, but not its people, is seen as increasingly aligned with Russia’s). Tourism from Western countries is robust and growing.

Georgia has had to defend itself against “marauders” from all sides partly because of its premium location along the Silk Route – on the crossroads of Asia and Europe. Perhaps for that reason the wise Georgian spirit has strengthened without losing its native charm.

Maybe the mischievous smile I noticed on so many people during my visit is a result of those adversities. I can’t be certain, but what I do know is how much I enjoy the good cheer that emanates all around in Georgia.

Eating–and drinking–the nation of Georgia

Over the centuries, the invaders and Silk Route traders have brought influences that have created a rich, complex, and delicious food culture.

Xiao long bao from Asia have here become khinkali, huge hand-held soup dumplings. You pick them up by the twisted handle of dough on top, hover it over your mouth, take a small nip out of the bottom, and slurp out the soup. Cilantro, called coriander here, and used to decorate all kinds of dishes, has also migrated from Asia. Iran brought pomegranates, Turkey gave Georgia kabobs. Kachipuri – cheese-stuffed bread taking many forms, including a boat shape topped with a sunny side up egg – has come from who knows where, maybe an amalgamation of many influences.

Not walnuts, though. Walnuts have been in the region for millennia, used to provide flavor, subsistence, and richness through times of scarcity. Walnuts enrich a plethora of Georgian dishes, from the multi-colored vegetable pkhali to churchkela, a breakfast/dessert/snack that’s a melding of walnuts and winemaking traditions that uses grape must (pre-fermented juice) and molasses to make a candle-shaped treat.

Then there’s the wine. With 8,000 provable years of winemaking, Georgia probably has the longest winemaking tradition in the world, and uses unique techniques that are all its own. It practices them to this day.

Georgia Wine, Food, and Culture in a Day

Back to my tour. I’m focusing on this adventure, undertaken in a single day, because it manages to pack in so much of the Georgian culture—the food, the wine, the feast called the supra, including homespun music and dancing. EatThis!Tours’ one-day overview provided a fantastic way to get out and experience Georgia’s rich countryside and culture.

Within 30 minutes of leaving Tbilisi, we were visiting historic sites and sitting down to drink wines with local winery owners and winemakers, sometimes in their own homes.

©BethEllen Clausen

Historic Winemaking and UNESCO-Recognized Qvevri

Our tour took us through the winding cobblestone roads of Sighnaghi, past a significantly long bas-relief mural depicting Georgian village life and World War II history. It stands as a memorial to those killed.

At the top of a hill, we paused in front of Kerovani Wine Cellar. We had a warm welcome and introduction here before stepping inside.

You can’t visit Georgia without encountering the ubiquitous qvevri buried in the ground. These egg-shaped clay amphora, (UNESCO-recognized since 2013), remain at stable temperature for fermenting and aging wine and are designed for the uniquely Georgian style of fermentation. Red and white wines are fermented along with the grape skin, seeds, and stems. When used for white wines, it is referred to as amber wine because of the beautiful color it produces.

Qvevri Disaster Averted

As we toured the wine cellar qvevris underfoot, I barely missed the inside of one as we navigated between Kerovani’s qvevri. My only excuse was the intoxicatingly delicious wines we had already tasted here, plus those we enjoyed at our prior stop. Luckily, an embarrassing disaster was avoided.

Anyway, the pointed bottoms of these giant clay eggs allow for seeds and then stems to sink and sit without having more contact with the juice than desired. After fermentation is complete, the skins float on top of the juice. The winemakers decide whether to stir for more contact, and when and if the solids will be removed while the juice ferments or ages.

The tannins extracted from all of these solids more than make up for those that would be provided by oak barrels that impart tannins in other wines. In addition, they act as natural stabilizers—antibiotics or antioxidants, if you will—to preserve the wine for a longer life. Even the cherrywood brushes used to scrub clean the qvevri have antibiotic properties, keeping the process close to nature.

While it’s true that some winemakers in Georgia use more modern European techniques and equipment (sometimes both are employed in the same winery), the traditional methods are holding fast.

©BethEllen Clausen

Another Layer of History

The owner invited me down into their museum of sorts—a room filled with artifacts uncovered when excavating another level below. Excavations like this are how we know the eight-millennia-long tradition of winemaking here, making Georgia “the cradle of wine.”

Pieces of wine-stained qvevri were uncovered south of Tbilisi dating back to 6000 BCE. Kakheti, the region we are in, is now the most productive and important for Georgian wine. It is about a 60-90 minute drive from the Neolithic archaeological sites.

Then, the wines themselves.

We taste everything from an orange pet-nat (a naturally sparkling, fruity charmer), designed to drink young and fresh while still bursting with bright fruit flavors, to heavier, more tannin-filled amber wines. They are meant to drink with meats, roasted vegetables, and heavier fare. Like the qvevri, amber wines are everywhere, and you’d be hard-pressed not to drink them. The green and red spreads of a variety of vegetables mixed with spices and walnut (pkhali), on toast, the family serves us, are just as engaging as the Georgian wine.

Saying kargad (“be well”) to depart from this comfortable living room/tasting room was not easy.

Cultural Immersion at Giuaani Winery

A quick skip from Tbilisi, at Giuaani Winery, we experienced an even deeper kind of Georgian hospitality. It was enchanting to taste the wines at this more modern facility, brimming with guesthouses, populated with colorful, traditionally garbed visitors, and featuring an afternoon mini-supra, or feast, led by a tamada, or toastmaster.

Adding to the charm, even though February was upon us, were the Christmas decorations that lingered. Unique 3-D farm animal scenes, ensconced in elevated lighting fixtures and a Christmas tree, lit up the room. Granted, Georgians observe the Julian calendar and celebrate Orthodox Christmas for a month, ending about a week into January, but these were the only celebratory signs of the holiday I encountered during my visit, and I was happy I did.

At supra, you experience true Georgian hospitality. You become family. We were taken under the wing of our tour guide and toastmaster Giorgi. Teaching us the history of the Kartli (what the Georgian people call themselves) and the roots of the language (not Slavic) was second nature to Giorgi.

Much of the cultural history is very much alive. It was played out during our visit with storytelling, numerous toasts, and feasting on traditional dishes. Thankfully, we were spared from the ritual of the ram’s horn, filled to the brim with wine, which you must drain straight to your gullet.

You might also enjoy:

Wines to Make Your Head Spin

The wine selection was expansive here. They range from quite light whites like the aromatic Kisi, to the orchard fruit and mineral-driven Mtsvane, to the heavier and most common of all, Rkatsiteli, made without the signature skin contact.

We move to amber wines made from the same varieties with nuttiness and more heft and structure, to full-bodied Saperavi that is Georgia’s own and most famous. Saperavi is an uncommon teinturier variety of grape, meaning the flesh inside this red fruit is red also, lending additional color and oomph to the wine. These wines can make your head spin.

Amber wine is Georgia’s signature wine. Made for millennia, it is similar to what other countries call orange wine, only more so. As with red wines, the white grapes are fermented on the skin. Here, they are additionally aged in qvevri, with skin, seed, and stem included. This produces a beautifully amber colored wine that has body and tannin more like a red. Amber wines fill many glasses at Georgia’s wine bars and supras.

Leaving this winery, I ran into a local guest carrying his small son in his arms. The child was wrapped in a fluffy yellow-hooded coat, his cheeks reddened from the northern chill. I was reminded of what draws me to travel to new destinations. I asked for a photo.

The image will warm any chill in my cheeks for years to come.

©BethEllen Clausen

At Home for a Supra

To top off our extraordinary day, we visit a family in a rural neighborhood. The son is the keeper of the perfectly chilled qvevris, buried in their yard until the wine is sufficiently aged.

The evening starts just like visiting a friend’s house for the first time. Bacho, the son and winemaker, gives a brief tour of the grounds, the small hibachi-sized grill covering grapevine wood from the vineyard. Smoking away, the grape wood imparts special flavors to the meat, with nothing in the vineyard going to waste. Sustainability, celebratory feasting, and natural winemaking go hand in hand in this unique culture.

Bacho then takes us into the kitchen, where the stove is topped with traditional stews. Nuts are being chopped for a sweet dessert. The kitchen table is covered in cheeses, bite-sized bread, and walnuts. Mom pours us a hot spiced wine topped with orange to warm us, belly first.

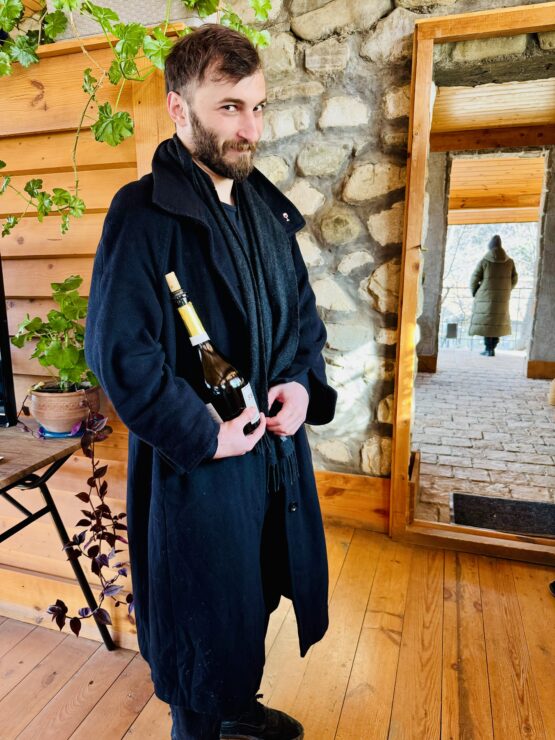

Here we also have a peek at some of the wines to be served throughout the evening, a handful of bottles lined up and all made in their modest homespun winery.

As we move to the dining room table, cozy elbow to elbow, close to the red embers in the wood stove, we glimpse more of the dishes we will indulge in. Our wine glasses are filled, of course, and the supra begins.

A True Tamada

Our host Bacho acts as tamada, a toastmaster of sorts. He discusses his family’s roots and tells stories of the culture. Each is capped with a garmarjos, or cheers, the literal translation being “to victory.” It’s another reference to Georgia’s resilience in fighting off invasions.

Before long, the family was engaged in song, some of the most heartfelt and moving singing I’ve experienced. Harmonic and emotional, the two elders sang, and their grandson played guitar. The music itself enraptured their guests.

Stories continued as well, Bacho encouraging each diner to contribute, as is the custom of the tamada. One young guest, inspired to tell us about her grandma’s cooking, breaks into tears. I realized that, with tears soon in everyone’s eyes, the supra acts as a community tapestry. It keeps the family fabric strong and constantly adjusts for new threads to be woven in.

The feasting continues, family wines are consumed in copious amounts, and grandfather and grandson move to the piano. Some are up on their feet dancing, others too stuffed to stand— all satiated, body, mind, and soul.

I was reminded of the statue of Kartlis Deda, the Mother of Georgians. She stands tall on a hill overlooking Tbilisi, holding a cup of wine in one hand to welcome friendly visitors. A sword is in the other to dispatch foes.

©BethEllen Clausen

If You Go

Getting to Georgia will take about 15-20 hours, including layover from the U.S. Lufthansa and United offer flights to Tbilisi from Munich or Zurich.

If you can avoid flying through Istanbul, I would. It’s a huge airport, and if you have a short layover, Turkish Airlines can be unforgiving. I missed my return connection by two minutes after boarding closed because I used the restroom. They refused to book me on another flight without buying another last-minute full-fare ticket.

Useful Links:

Georgia International Travel Information from the U.S. Department of State

Wineries visited:

Guest suites are available at Giuaani Winery here.

BethEllen Clausen blogs at OrganicWineTravel.